Roca Vecchia: a Mediterranean hub through history

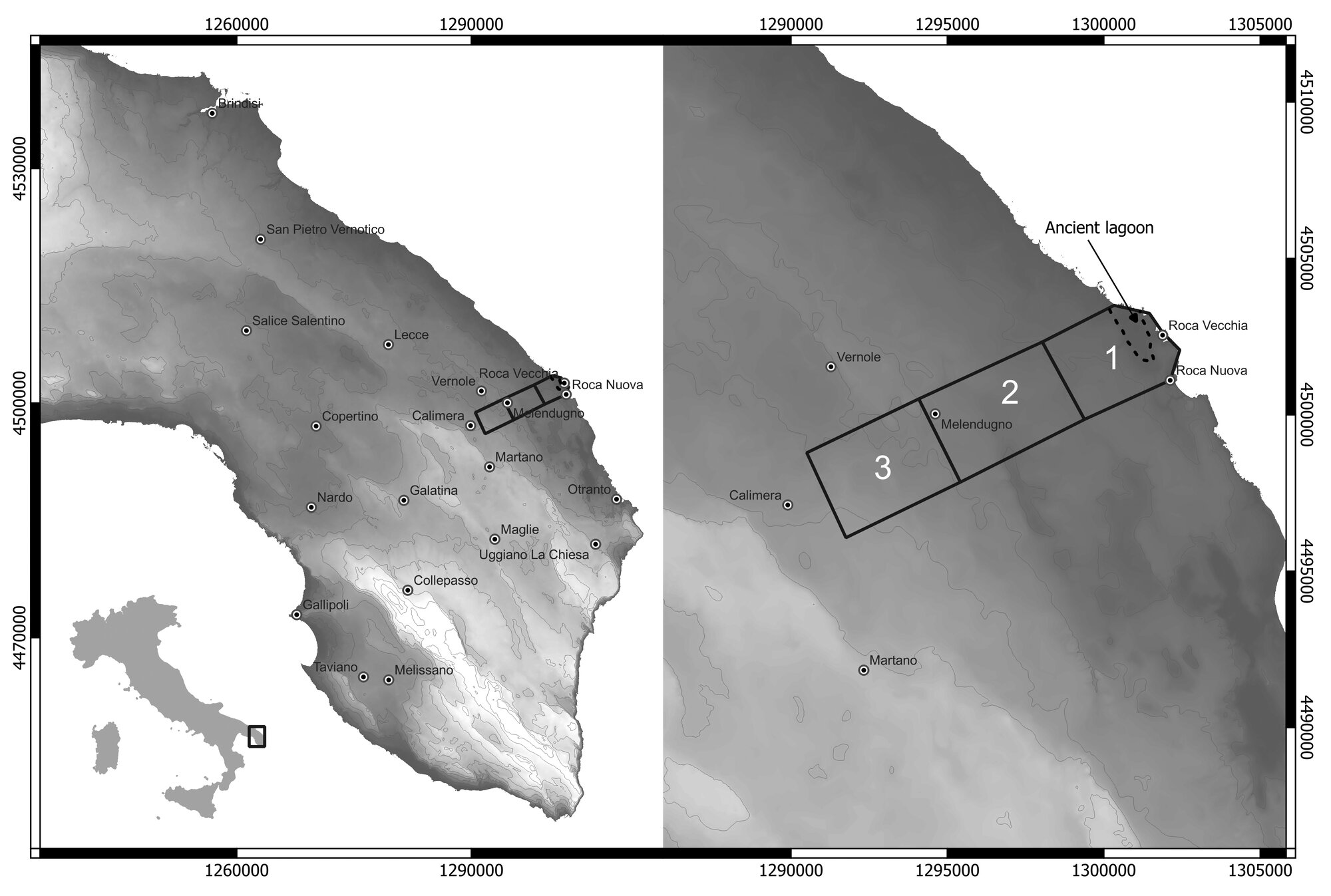

The archaeological site of Roca Vecchia is located on the Adriatic coast in southeastern Italy (Figure. 1). The site has been one of the most important mobility and interaction hubs in the central Mediterranean Sea since later prehistory, when it was at the core of connections with Aegean palaces. It later developed through ancient times as important cave-sanctuary and, in the Medieval Age, it became a military citadel.

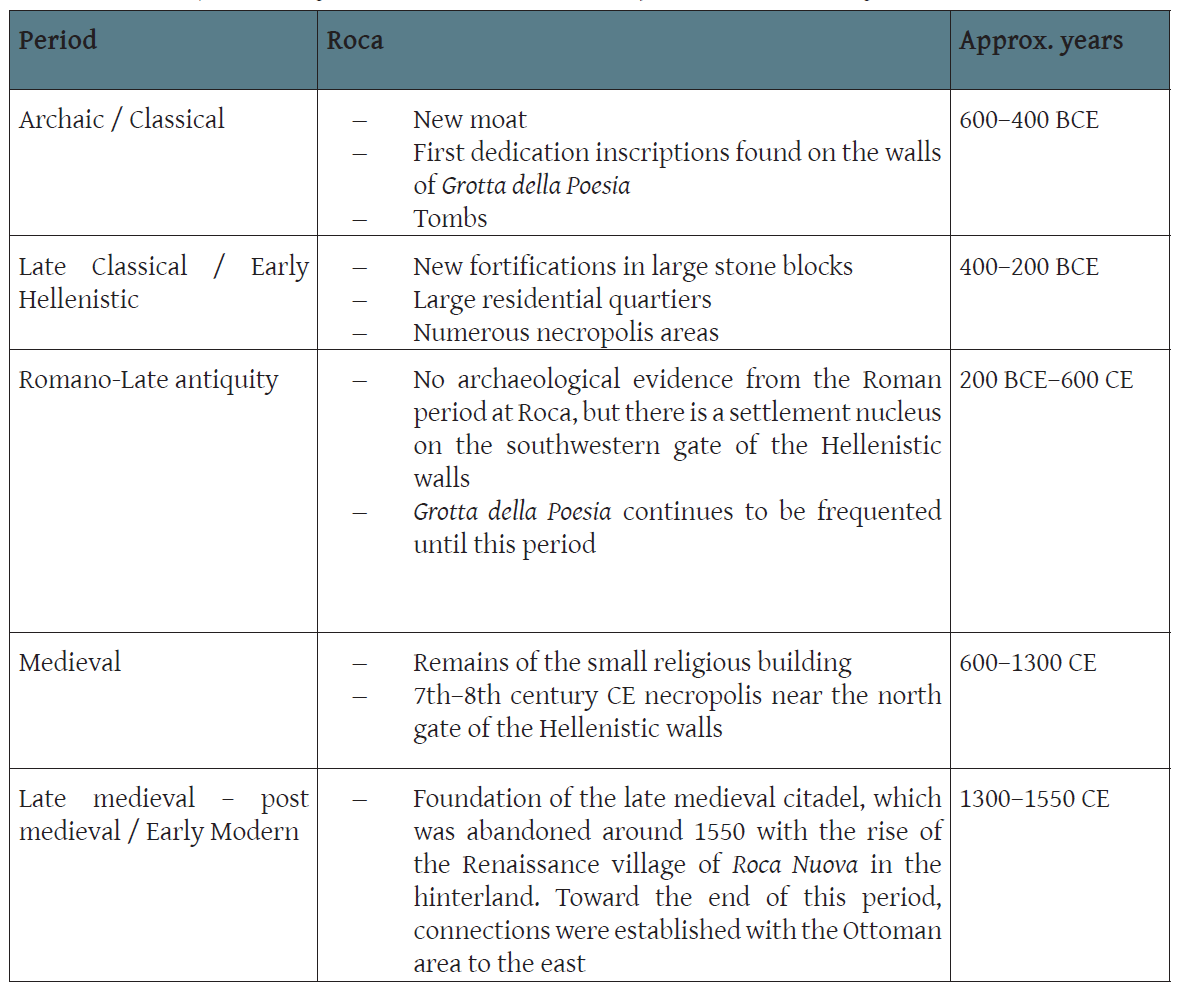

The main objectives and methodology of the Roca Archaeological Survey 1 were outlined in Part I of this article, published in Groma 8 (Iacono et al. 2024), along with the preliminary results related to the Prehistoric phases of the site. This paper will focus on the Ancient to post-medieval / Early Modern macro-periods Table 1), trying to highlight how the specific features of a mobility hub like Roca Vecchia influenced occupation through time.

Extensive connections during the Archaic and Hellenistic period are witnessed not only by imported materials recovered at the site, as well as at its necropoleis (Giannotta 1996; Auriemma 2004), but also in the nearby Grotta della Poesia, whose walls are covered by numerous inscriptions in three different languages: Messapian, Greek and Latin (Pagliara 1987, see also Auriemma 2004). Finally, the late-medieval and post-medieval phases are best represented in the architectural remains currently visible on the ground, which have allowed an accurate reconstruction of this historical phase of the settlement (Güll 2008). Beyond the evidence from the main settlement, forcibly abandoned in favour of an inland new village around the late 16th century CE, for a long time the hinterland of Roca saw also other forms of mobility. These can certainly be recognised in the medieval and post-medieval periods when the entire eastern Salento experienced the arrival and settlement of people who spoke the Griko language (a form of Greek attested in various parts of Southern Italy, see Pellegrino 2021) and who had considerable religious, cultural and economic ties with the world on the other side of the Adriatic Sea (i.e. Greece and the Balkans).

After the abandonment of the main medieval citadel, not much is known about Roca. Between the 1200s and 1800s the lagoon environmental conditions worsened considerably, creating relevant economic issues in the area as reported by local historical sources (Carrozzo 2019). At some point after this period, the village of Roca “Li posti” was established although this remained very small (it had only 21 inhabitants up until 2001). In the 1950s, a summer camp/leisure facility was established by the local church, later reused in the 1990s to guest migrants coming from Albania in the first main immigration flow occurring in Europe in the aftermath of the fall of the Eastern Bloc (Farina and Iacono 2024). More recently, the wider area has been at the centre of a very intense social and political conflict between local communities and large-scale development, following the decision to route the large pipeline bringing to Europe Azerbaijani gas (the trans-Adriatic pipeline) through this region.

The Landscape of Roca Vecchia through time

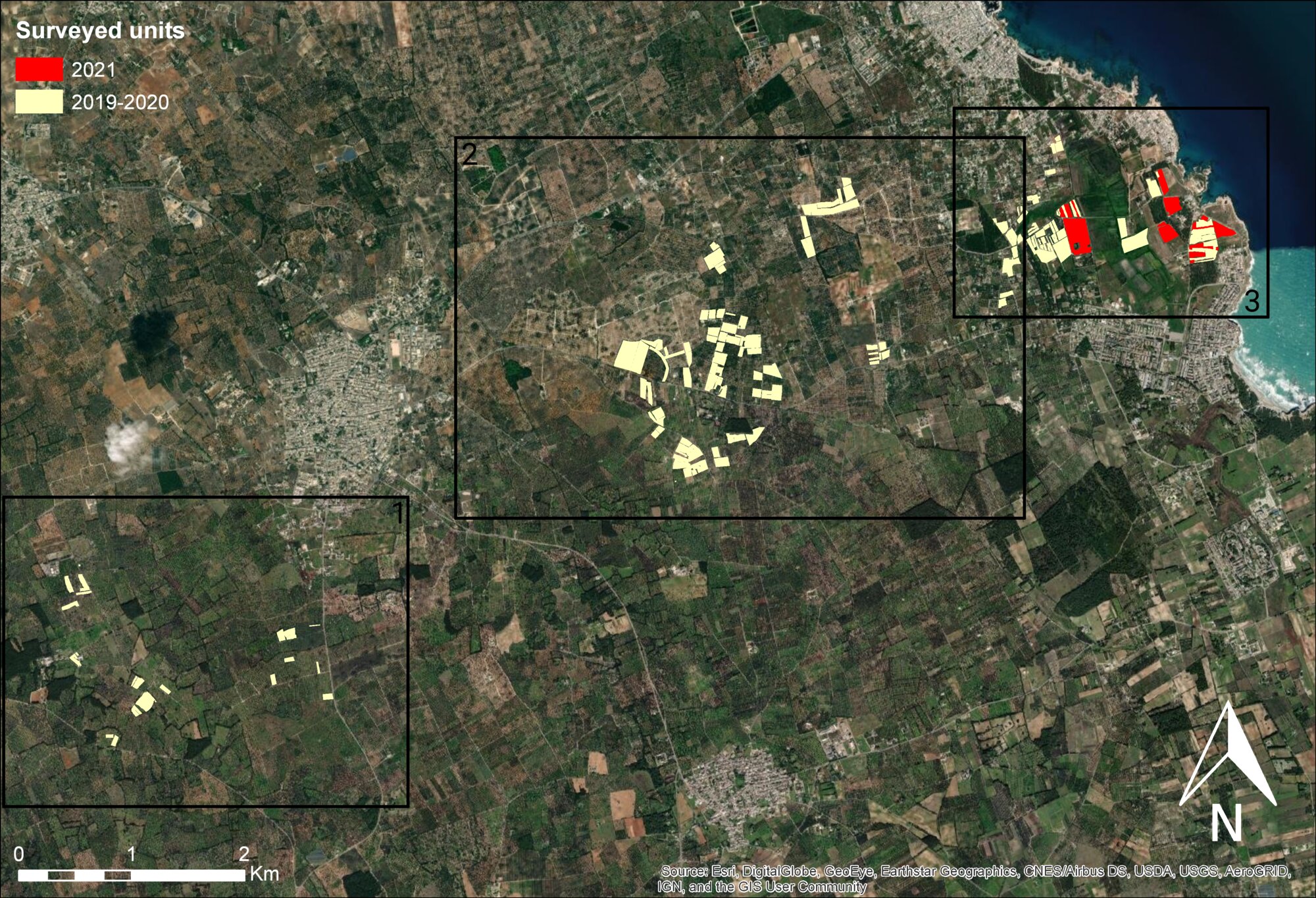

A discussion on the field methods and quantification practices employed for material collection was presented in the previous part of this article Figure. 2Iacono et al. 2024). Here, we will focus only on the data pertaining to periods ranging from Antiquity to post-medieval times (Table 1).

From the Archaic period to Late Antiquity

After the Iron Age, for which there is scarce evidence (for the few well-explored contexts dating to this period from the main site, see Corretti et al. 2017), more substantial information on the human presence at the site can be found from the 4th century BCE onward. The settlement’s extension included the area of the promontory where the prehistoric occupation was concentrated. This area is provided with fortification walls that describe an open polygon approximately 1550 m in length, with two entrances: the North and West Gates. Two ditches run parallel to it, whose cuts are evident along the cliff (Rizzo 2006; De Giosa 2011).

Fortification walls display several phases of construction and appear to have been interrupted simultaneously in all sectors. Their chronology, spanning from the second half of the 4th to the beginning of the 2nd century BCE, could be estimated thanks to the discovery of a tomb below the foundation level (De Giosa 2011). At this point, Roca Vecchia is a Hellenistic town, and the surface record poses no little interpretative issues (Bintliff 2012, and more generally Vermuelen et al. 2012). The quantity of materials has expanded tenfold, particularly in the area immediately to the south of the Bronze Age fortification. Moreover, the presence of formal burial areas and structural remains, excavated by Mario Bernardini in the 1940s and 1950s (Bernardini 1956; Giannotta 1995, 1996), further complicates the analysis.

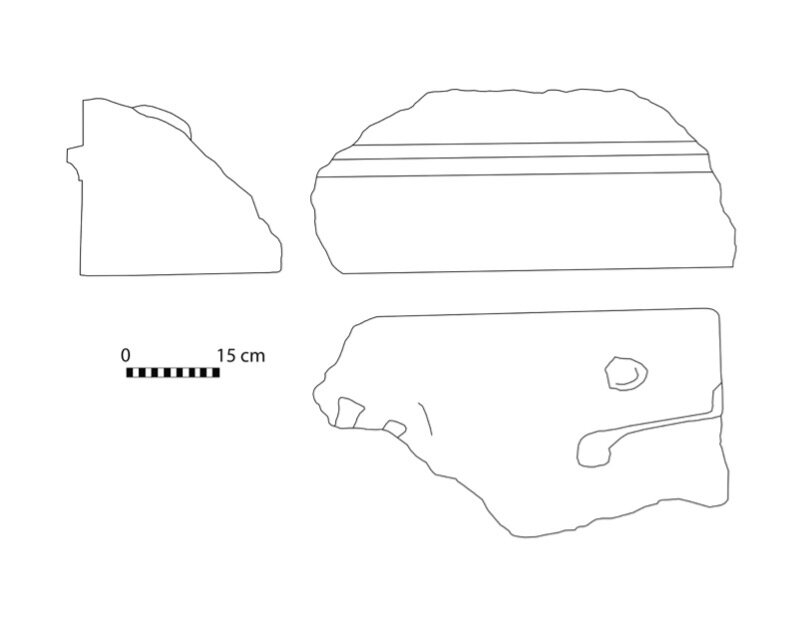

Six architectural elements dating to this broad chronological horizon have been identified in the surroundings of the wall circuit, namely a keystone, a base element, a cornice, the fragment of a threshold, and some slabs. These could have been part of the nearby monumental necropolis complex. All analysed pieces are made of fine-grained tuff, probably from quarry deposits near the Roca area.

The cornice (Figure. 3) probably belonged to a prestigious monumental tomb comparable to others already identified in the area (Lamboley 1988). Comparative analysis with other findings from the area will help to determine if these are local artefacts, and therefore is they were produced by local workers or whether they were imported. It is possible to roughly date the architectural elements to a broad chronological period from the second half of the 4th to the beginning of the 2nd century BCE.

As for the internal organisation of the settlement, the remains of a rectangular structure were found in the central sector of the promontory, which retains part of the foundations, several blocks, and a limestone floor (Pagliara 2001). Immediately to the north and south of the building, along its shorter sides, two roadbeds - used for at least a century – have been identified. Structures and tombs belonging to the same chronological horizon have also been uncovered along the southern side of the inlet opposite the Sanctuary of the Madonna di Roca and to the SW of the Grotta della Poesia, SE of the promontory (Pagliara et al. 2009). In this area, excavations have revealed a complex urban layout, including the terminal part of a moat dug into the bedrock dating to the Late Archaic phase (late 6th century BCE). Running parallel to this moat there was a straight road axis, on the sides of which a series of rectangular rooms and enclosures were located. From the same road, two additional orthogonal paths departed northward, and between them another series of rooms and structures were found. Finally, in the same sector, 22 pits and tombs dug in the bedrock were brought to light (De Giosa 2011).

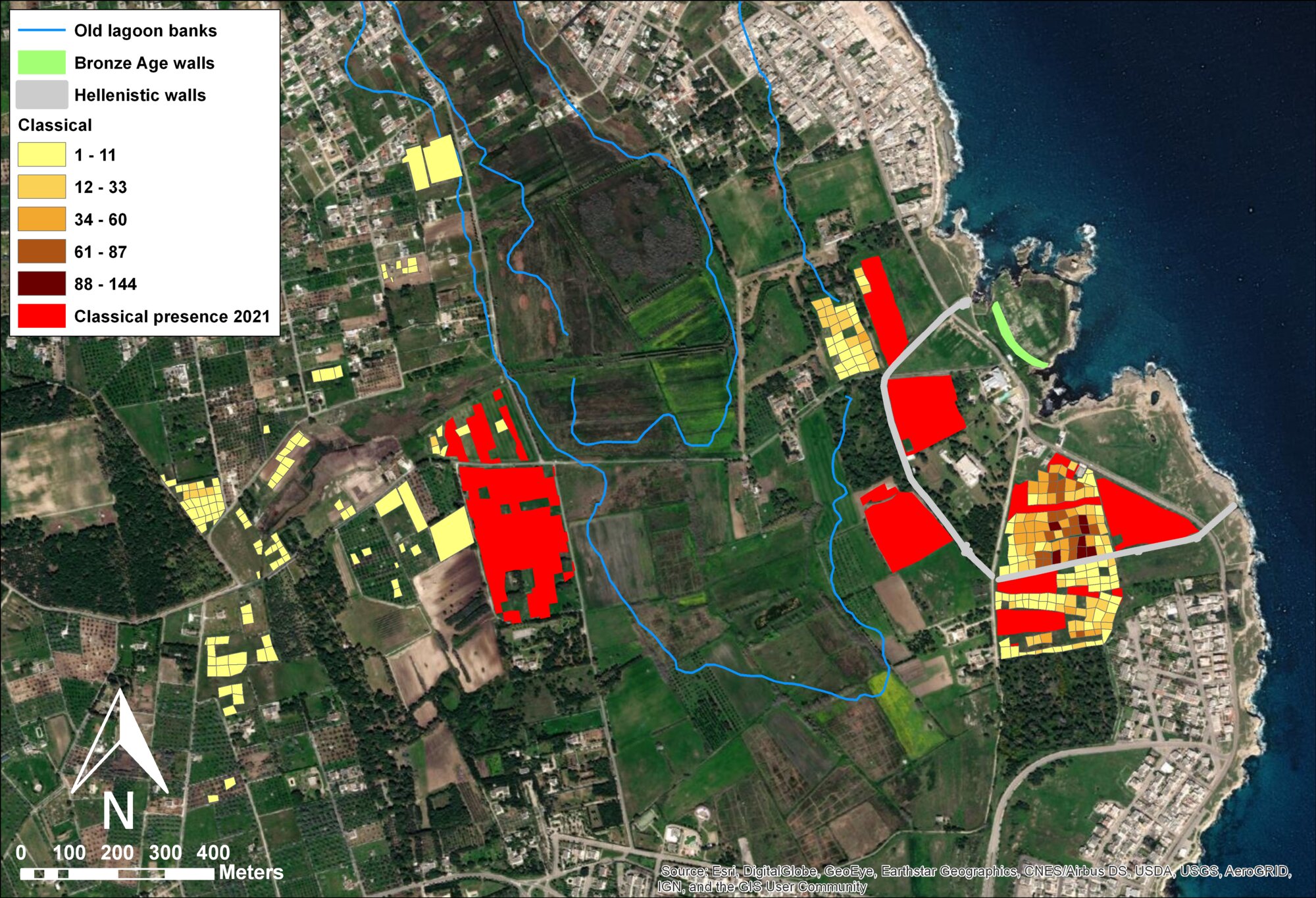

A subsample of the material culture collected during the 2020 survey ( Figure. 4 - Figure. 5) has been analysed and is predominantly composed of non-diagnostic finds or finds with broad date ranges, which hinder precise chronological interpretation. Some ceramic classes, such as plain and cooking wares, are particularly difficult to assign to specific chronological phases. In this section, we primarily discuss finds recovered in the immediate surroundings of the main site (Fig. 5).

The Archaic and early Classical phases (second half of the 8th to the early 5th century BCE) at Roca Vecchia are documented by limited diagnostic finds, including fine wares, trade amphorae, and local matt painted pottery (18 certain finds and 11 dubious ones). Among the Archaic fine pottery, a wall fragment of a so-called filetti cup, characterised by a grey fabric, could be tentatively considered one of the earliest examples. Also, a rim of B2 type cup, widely attested in colonial and indigenous contexts of south Italy in the 6th century BCE, is noteworthy. A single fragment of Black-Figure Greek pottery was uncovered during the survey. Other finds, such as black gloss and slipped pottery - primarily lekanai - could hypothetically be associated with this period based on the features of their fabric (e.g., ‘sandwich’ type or gray) and surface treatment. At present, we do not have enough evidence to determine whether such early materials represent Greek imports from ‘colonial’ regions, though they undoubtedly testify to mobility typical of the mid-first millennium BCE in Southern Italy.

Trade amphorae are represented by very few fragments associated with Greek imports commonly documented in Archaic South Apulia, such as a toe and a handle consistent with a Corinthian Amphora A, and a toe belonging to a Corinthian B (Koehler 1981).

The evidence datable with certainty to the full 5th century BCE is very scarce. A fragment of red-figure stamnos and an almond-type rim belonging to a plain basin (see parallels in Villing and Pemberton 2010, 576, Fig. 9 nos. 15-16) can be tentatively associated to this phase.

Much more documented is the evidence for the Hellenistic period (at least 84 fragments), proving a more intense presence in the area from the 4th to the 2nd century BCE. Black gloss wares, either produced locally or in the nearby Greek poleis of Metaponto and Taras, are documented by a broad variety of drinking vessels, namely skyphoi (type Morel 4375b 1, 4373), one-handled and handleless cups (type Morel 2942), concave-convex type, small cups (Morel 2400, 2430), kantharoi (Morel type 3164 a 1), shallow bowls (Morel type 2273-2274-2276), and plates (Morel type 1313-1315) 2. A single fragment of Hellenistic Red-Figure pottery produced in the colonial area occurred with certainty. Among other fine wares, there is an abundance of wall, bases, and handles fragments from kraters, basins, and plates belonging to the Hellenistic Messapian painted pottery, characterised by a brown or red coat and stripes. The presence of other local fine pottery productions, like the Grey Gloss Ware and the High Fired Ware group (HFWG) is also documented by a few finds.

Fragments of plain wares, associated primarily with the same forms attested in painted wares and related to household contexts, are also numerous. Some of these could also come from tombs grave goods. Additionally, eight fragments of cooking wares are also related to domestic contexts and consistent with shapes and types commonly attested in the Hellenistic sites in Messapia, predominantly chytrai, lids (to a lesser extent), as well as a lopas.

The so-called ‘Graeco-Italic’ and ‘mushroom-rimmed’ amphorae (at least 19 items) are the most common types found among transport vessels. These amphorae were very popular in the Mediterranean area from the end of the 5th/early 4th century BCE onward with different production centres located in the Aegean area and in Southern Italy (Vandermersch 1994; Lawall 2004). Less frequently attested are other types of Hellenistic amphorae, including a fragment of late Punic Maña C, few fragments belonging to late Roman Republican amphorae Lamboglia 2 (see Bruno 1995), and a toe from a probable ‘Brindisi’ type amphora (Sciallano and Sibella 1991).

From the 1st century BCE onwards, through the entire Roman period, there is a drastic decrease in the number of finds. Only four fragments of fine pottery certainly belonging to this phase have been collected during the survey; a foot of Eastern Sigillata A (forma 23, 2nd c. BCE–10 CE; Atlante II, 24, pl. 3, no. 14), a wall of African Sigillata C dated to 4th century CE (type Hayes 62 A or B; Atlante I, pl. 26, no. 15), a fragment of African Sigillata D of 5th century CE, and a wall of thin-walled pottery. The number of Roman transport amphorae is equally modest (10 fragments, only two of them attributable with confidence), and most of them consistent with African production, although some could be associated with the earlier late Punic productions.

Likewise, the evidence for the Late Roman phase is scant, consisting in only a fragment of a transport amphora of dubious provenance (possibly Africa or from the Aegean area) and a rim of bowl/lid belonging to a cooking ware type generically attested in the Mediterranean between the 5th and the 7th century CE.

This picture confirms what was already known from the excavation at the main site, indicating that Roca was abandoned and seems to have remained uninhabited throughout the entire period of Roman occupation in Salento (Auriemma 2004, 199). It was only in the Middle Ages that the site resumed occupation.

Medieval and post‑medieval times

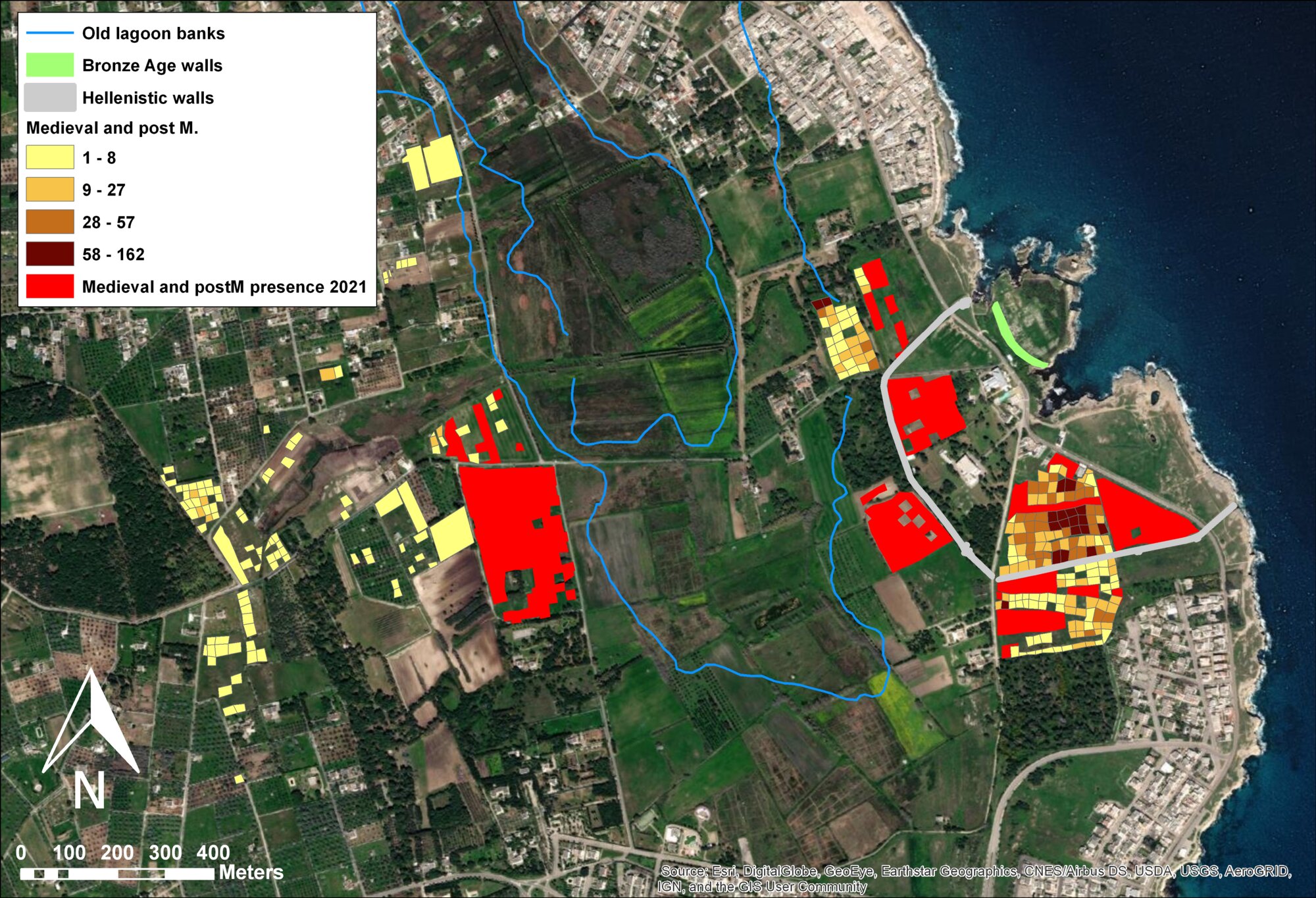

The material dating to the medieval and post-medieval periods consists of fragmentary finds, many of which presents challenges in typological identification. Its distribution is somewhat more evenly widespread when compared to earlier periods (Figure. 6 - Figure. 7), possibly due to the presence of the early modern settlement of Roca Nuova in the deep hinterland of Roca Vecchia, at least from the mid-late 16th century CE (see Fig. 6).

The history of Roca Vecchia in the Byzantine period remains to be defined. The only available evidence comes from numismatic sources, with the discovery of a bronze folle coined between the 10th and the first half of the 12th century CE (Auriemma and De Gasperi 2003, 78).

Some amphora fragments with thick walls and fabric rich in white or black inclusions, likely micaceous, could be attributed to an early medieval period. The existence of a small church with burials near the north gate, still unpublished but attributed to the early medieval period, further supports the idea that the site was already frequented during this period.

Regarding the data collected through the survey, most of the materials consist of tile fragments that can generally be attributed to the medieval and post-medieval periods. These are difficult to date precisely, though published data from the late medieval occupation of Roca Vecchia provide a chronology ranging between 14th and 16th centuries.

This material is composed of mainly locally produced ceramics circulating in the area during the medieval and post-medieval period, although imported materials are also attested, highlighting the importance of Roca as a trade hub in the southern Adriatic area during this time. Among these finds, some fragments of graffita (Fig. 7) dating probably to the second half of the 16th century CE seem to have been imported from various regions of northern Italy, suggesting previously unrecognized forms of long-range mobility. The ceramic material is dominated by depurated, unpainted, everyday pottery, with some shreds painted in narrow bands. These artefacts are characterised by highly depurated clays and are uncoated, intended for the storage of solid or liquid food (in the case of closed shapes) and for the preparation of raw food (in the case of open shapes). Among the diagnostic fragments, one is a rim of a large open shape container (basin) characterised by a short jutting brim with a triangular crosssection, widespread in the period between the 14th and 16th centuries CE (Güll 2008, 405-407; Kulja 2013, 155-157).

Oval-section handles and ribbon handles of large containers with a truncated cone or globular profile have been identified. These were widely attested throughout the Middle Ages, with a particular high incidence in the late medieval phase, especially at sites in the Salento hinterland, namely Apigliano, Quattro Macine, Cutrofiano, Lecce and Muro Leccese (Caprino 2017, Tagliente 2007). These materials provide evidence for the existence of medium-scale market exchange and the associated forms of mobility.

There is a rather limited number of fragments related to cooking ware, both with or without lead-based glaze. Despite the high fragmentation, it was nevertheless possible to recognise closed shapes referable to pots with a globular shiny glazing (preserved to varying degree) body and two close vertical handles. The presence of the glazing serves as a reliable chronological marker considering that this technique does not appear to be attested in contexts predating the 14th century CE (Caprino 2006; Güll 2008; Kulja 2013; Kulja 2015).

Polychrome glazed pottery is attested by very few fragments. Of particular interest is a jug with a decoration consisting of brown and red parallel strokes, a motif widely documented both in Roca Vecchia and inland sites, and dated to the 14th century (Figure. 8; Güll 2008, 394-397; Tinelli 2012; Kulja 2013; Kulja 2015).

The assemblage also includes fragments of tobacco pipes, objects of Ottoman tradition that are frequently found in both urban and rural contexts of the modern age throughout Apulia. Their presence suggests the cultural significance and influence of interactions with the Eastern side of the Adriatic - then part of the Ottoman empire – and the possible impact on market exchanges and personal mobility. The two fragments recovered are both pertinent to plain pipes and can be classified as Type 1, thus characterised by a clear distinction between the burner and the short pipe (Bruno 2015; Kulja 2016).

Mobility in the long term at Roca Vecchia

Moving to historical times, we start to glimpse the image of a Hellenistic city at Roca Vecchia, whose functioning relied on both short- and long-range mobility. As far as the short-range is concerned, it is reasonable to assume daily movements toward fields for agricultural activities essential to sustaining a nucleated settlement. It is no coincidence that the imposing ancient fortifications were suitably equipped with gates – some more monumental than others – designed to facilitate such movement (De Giosa 2011). Conversely, long-range mobility involving both relocation of individuals and commercial trade is evidenced by the circulation of imported material from nearby Greek colonies and other Mediterranean regions, as well as by the epigraphic inscriptions in multiple languages inside Grotta della Poesia (Pagliara 1987). Despite the continued use of Grotta della Poesia, the Roman period appears to mark a potential hiatus in the occupation of the site and a shift in settlement patterns, with people leaving Roca to relocate toward the surroundings north and south areas. A previously fertile landscape is now apparently abandoned (Auriemma 2004, 199).

Following Roman times, evidence of mobility within the landscape is rather scarce up to late medieval times. However, coin finds and the presence of a Byzantine cult building at the main site certainly tells us of eastward connections, which undoubtedly involved human mobility as well (Auriemma and De Gasperi 2003; De Pascalis 2004). When the Norman city was founded in later medieval times, it is possible to suggest that this involved the relocation of the population who occupied the area until its eventual abandonment (De Pascalis 2004; Güll 2008). Material remains datable to the modern period attest to the prosperity of regional market exchanges linking Roca Vecchia to nearby production centres as well as to more remote regions, such as northern Italy and the Ottoman Empire. The latter connection also facilitated the gradual diffusion of cultural practices, including tobacco smoking, toward Western Europe.

Conclusions

A long-term analysis of mobility patterns at Roca Vecchia provides broader insights into the interaction between human landscapes and mobility from Prehistory to modern times. As discussed in Part I of this contribution, the analysis of surface finds attests to a transition from localised Prehistoric mobility to increasingly larger settlements, indicating that by the end of the Bronze Age these communities were more “urbanised” than previously assumed (Iacono et al. 2024).

As we transition into historical times, the evidence of mobility in the landscape become even more pronounced, as examined in this paper. The presence of materials from different Mediterranean regions suggests long-distance exchanges, while short-range mobility may be reflected in settlement nucleation and the gradual expansion of the site’s boundaries. However, given the scarcity of topographical data for the Iron Age, assessing the continuity between the site’s extent in the Bronze Age and its size in Classical times remains challenging.

The expansion of settlements and their associated networks was not a linear process. The apparent decline in occupation and mobility at Roca Vecchia during the Roman period suggests that such trends could undergo significant disruption or even reversals, whether temporary or permanent. Further research is required to better understand the impact of these changing dynamics within the Tamari basin (Fig. 5).

Footnotes

- The Roca Archaeological Survey was funded by the project “Landscape of Mobility and Memory” (Progetto Montalcini 1910) and AlmaScavi – University of Bologna. Permits were granted by the Superintendence ABAP for the provinces of Brindisi and Lecce. We thank the Institution and the many students who took part in the survey.

- For Morel types see Morel 1981.

References

- Atlante I (1981) – Enciclopedia dell’arte antica classica e orientale. Atlante delle forme ceramiche. I. Ceramica fine romana nel bacino mediterraneo (medio e tardo impero). Rome.

- Atlante II (1985) – Atlante delle forme ceramiche II. Ceramica fine romana nel bacino mediterraneo: Sigillate orientali. Rome.

- Auriemma, R. 2004. Salentum a salo. Porti, approdi, rotte e scambi lungo la costa adriatica salentina I–II. Galatina.

- Auriemma, R. and Degasperi, A. 2003. “Roca (Le), campagne di scavo 1987‑1995: rinvenimenti monetali”, Studi di Antichità 11, 73–124.

- Bartoloni, G. & Delpino, F. 2005. (ref. noted in table note).

- Bernardini, M. 1956. “Gli scavi di Rocavecchia dal 1945 al 1954”, Studi Salentini 1, 20–65.

- Bintliff, J.L. 2012. “Territoriality and Politics in the Prehistoric and Classical Aegean”, Archaeological Papers of the A.A.A. 22(1), 28–38.

- Bruno, B. 1995. Aspetti di storia economica della Cisalpina romana: le anfore di tipo Lamboglia 2. Rome: Quasar.

- Bruno, B. 2015. “Oggetti di abbigliamento e ornamento”, in Arthur, Leo Imperiale & Tinelli (eds), Apigliano... Lecce, 79–89.

- Caprino, P. 2006. “Appunti sulla ceramica da fuoco…” Quaderni del Museo della ceramica di Cutrofiano 10(2), 11–47.

- Caprino, P. 2017. “Ceramica medievale e post‑medievale”, in Arthur, Bruno & Alfarano (eds.), Archeologia urbana a Borgo Terra, I. Firenze, 93–135.

- Carrozzo, W. 2019. Terra Roce: Roca Nuova, storia di un passato ritrovato. Monteroni di Lecce.

- Corretti, A., Dinielli, G. & Merico, M. 2017. “L’età del Ferro nel sito di Roca…”, in Radina (ed.), Preistoria e Protostoria Della Puglia, 565–571.

- De Giosa, D. 2011. Le mura di Roca nel panorama dell’architettura militare messapica. PhD diss., Univ. del Salento.

- De Pascalis, D.G. 2004. “Una città di fondazione tra XIII e XIV secolo…”, in Casamento & Guidoni (eds.), L’urbanistica Delle Città Medievali Italiane, 304–314.

- Farina, E.B., Iacono, F. 2023. “Migration flows and concrete walls…”, World Archaeology 55(2), 206–226.

- Giannotta, M.T. 1995. “Rinvenimenti tombali da Rocavecchia (1934)…”, Studi di Antichità 8, 39–73.

- Giannotta, M.T. 1996. “Rinvenimenti tombali da Roca Vecchia (1934)…”, Studi di Antichità 9, 37–98.

- Güll, P. 2008. “Roca nel Basso Medioevo…”, Archeologia Medievale 35, 381–427.

- Iacono, F., Alessandri, L., Magrì, A., Ceccato, Z., Agostini, G., Spagnolo, V. & Salvin, A. 2024. “Landscape of Mobility: results of the Roca Archaeological Survey (Part 1)”, GROMA 8, 37–54.

- Koehler, C.G. 1981. “Corinthian developments…”, Hesperia 50(4), 449–458.

- Kulja, E. 2013. “Un’associazione di reperti…”, Annali SNS Pisa 5(2), 152–168.

- Kulja, E. 2015. “I reperti ceramici della torre”, in De Pascalis (ed.) Torre S. Caterina di Nardò, 34–41.

- Kulja, E. 2016. “Le pipe in terracotta…”, Archeologia Postmedievale 20, 97–107.

- Lamboley, J.L. 1988. “Edifice Funéraire…” Studi di Antichità 5: 161–175.

- Lawall, M. 2004. Amphoras Without Stamps… in ΣΤ´ επιστημονική συνάντηση…, 445–454. Athens.

- Morel, J.P. 1981. Céramique campanienne. Les formes. Rome: ÉFR.

- Pagliara, C. 1987. “La Grotta di Poesia…”, Annali SNS Pisa 17, 267–328.

- Pagliara, C. 2001. “Roca”, in Bibliografia Topografica… XVI, 197–229.

- Pagliara, C., Guglielmino, R. & Scarano, T. 2009. “Roca (Melendugno)…”, Rivista di Scienze Preistoriche LIX, 397–398.

- Pellegrino, M. 2021. Greek Language, Italian Landscape: Griko… Washington, DC.

- Rizzo, A. 2006. “Il contributo della fotografia aerea…”, Archeologia Aerea 2, 247–268.

- Sciallano, M. & Sibella, P. 1991. Amphores: Comment les identifier? Aix‑en‑Provence.

- Tagliente, P. 2007. “Lecce, ex Convento del Carmine…”, Archeologia Medievale 34, 147–168.

- Tinelli, M. 2012. “Produzione e circolazione della ceramica invetriata policroma…”, in Gelichi (ed.), LX Congresso Internazionale AIECM 2, Firenze, 515–517.

- Vandermersch, C. 1994. Vins et amphores de Grande Grèce et de Sicile. Naples.

- Vermeulen, F., Burgers, G.-J., Keay, S. & Corsi, C. (eds.) 2012. Urban Landscape Survey in Italy and the Mediterranean. Oxbow.

- Villing, A. & Pemberton, E.G. 2010. “Mortaria from Ancient Corinth…”, Hesperia 79, 555–638.

-

Figure 1 - Main area of the Roca Archaeological Survey (after Iacono et al. 2020).

Figure 1 - Main area of the Roca Archaeological Survey (after Iacono et al. 2020). -

Figure 2 - Surveyed units in the Roca Archaeological Survey according to date (Iacono et al. 2024).

Figure 2 - Surveyed units in the Roca Archaeological Survey according to date (Iacono et al. 2024). -

Figure 3 - Stone cornice from the ancient town (drawing by the author)

Figure 3 - Stone cornice from the ancient town (drawing by the author) -

Figure 4 - Distribution of ancient material in the areas 1-2 of Fig. 2

Figure 4 - Distribution of ancient material in the areas 1-2 of Fig. 2 -

Figure 5 - Distribution of ancient material in the area 3 of Fig. 2

Figure 5 - Distribution of ancient material in the area 3 of Fig. 2 -

Figure 6 - Distribution of medieval and post-medieval material in the areas 1-2 of Fig. 2

Figure 6 - Distribution of medieval and post-medieval material in the areas 1-2 of Fig. 2 -

Figure 7 - Graffita pottery

Figure 7 - Graffita pottery -

Figure 8 - Distribution of medieval and post-medieval material in the area 3 of Fig. 2

Figure 8 - Distribution of medieval and post-medieval material in the area 3 of Fig. 2 -

Tab 1 - Diachronic developments at Roca Vecchia (dates BCE in the table are only grossly approximate and do not take into account different opinions in chronological assessment of main developments such as the beginning of the Iron Age (on which see Bartoloni & Delpino 2005 or Picht & Nijoboer 2018)

Tab 1 - Diachronic developments at Roca Vecchia (dates BCE in the table are only grossly approximate and do not take into account different opinions in chronological assessment of main developments such as the beginning of the Iron Age (on which see Bartoloni & Delpino 2005 or Picht & Nijoboer 2018)